26

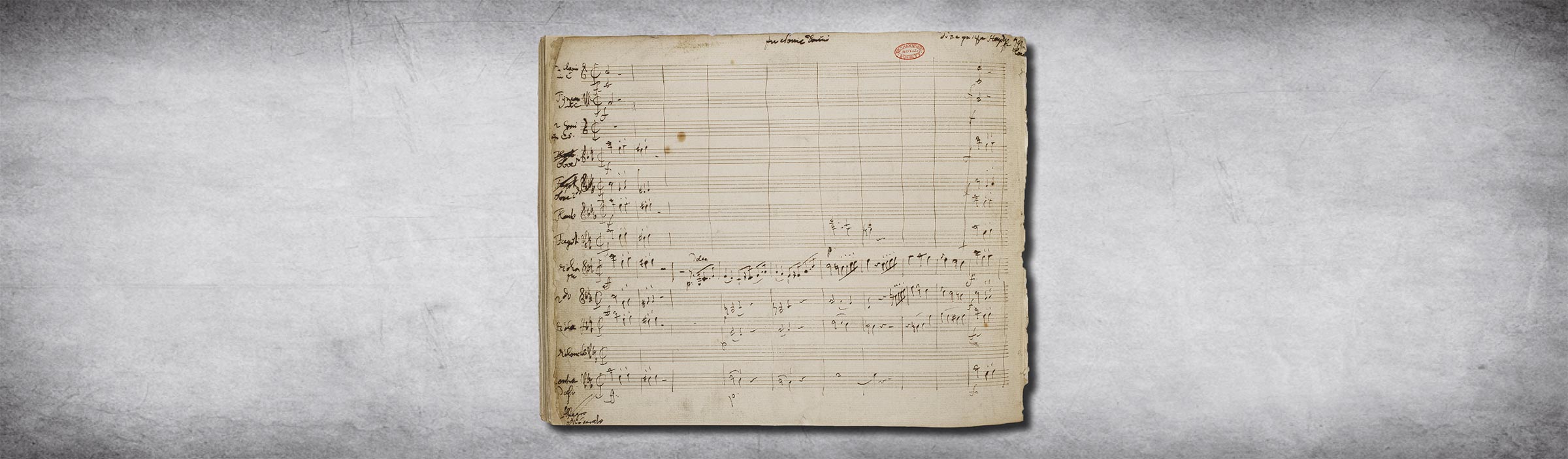

"Lamentatione"

d minor

Sinfonien um 1766-1769

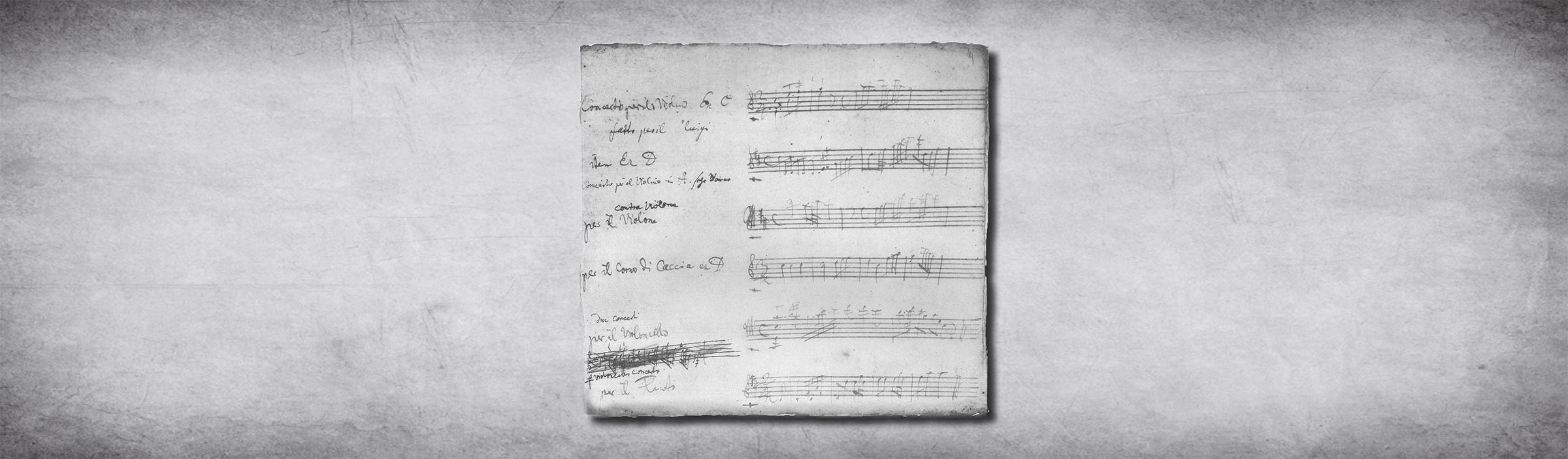

Herausgeber: Andreas Friesenhagen und Christin Heitmann; Reihe I, Band 5a; 2008, G. Henle Verlag München

Symphony No. 26 in D minor ("Lamentatione")

This three-movement work is an 'Easter' symphony. The oldest surviving source is headed 'Passio et Lamentatio', and the first two movements both utilize material from traditional Austrian musical dramatizations of the Passion.' Haydn's compositional strategies are correspondingly unusual.

The Allegro assai con spirito opens with a driving syncopated forte theme in Haydn's best early 'Sturm und Drang' style, followed by several halting piano phrases. Without warning, the music then shifts to the relative (F major), where the first liturgical theme is heard fortissimo in one oboe and the second violins. This theme has three sections: a 'declaiming' forte melody, based on a rhythmic ostinato; a stepwise piano melody in longer notes; and a higher variant of the declaiming melody. These correspond, respectively, to words of the Evangelist ('Passio Domini nostri Jesu Christi secundum Marcum. In illo tempore'), of Jesus ('Ego sum'), and of the Jews ('Jesum Nazarenum'). The whole is enveloped by constant quavers in the first violins, which maintain momentum and rhythmically link the theme to the larger context.

The relatively brief development is based primarily on the opening theme (though the words of Jesus are briefly recalled). The exposition is also recapitulated without change, until a dominant pedal 'portends' something unusual which proves to be a recapitulation of the entire second group in the tonic major (D major), Passion theme and all. Not only is this effect striking in its own right, but it is highly exceptional: this is the first minor-mode sonata-form movement that Haydn ended in the major, and he did not do so again until 1782. By thus ending in the 'wrong' mode, he surely intended not merely to quote an old Passion tune, but to invoke its significance: at once gruesome and hopeful.

A further consequence of this ending is that the Adagio enters with a remote tonal relation (F major from D major); again, Haydn had never done this before. The Adagio is also based on a (different) liturgical melody, also played by oboes and second violins, again 'haloed' by a descant in the first violins. But here this melody begins straight away. It is a true 'lamentation', taken from a collection of such melodies identified by letters of the Hebrew alphabet ('aleph'. 'beth', etc.); its text begins, 'Aleph. Incipit lamentatio Jeremiae Prophetae.' Haydn's setting, with the violin curlicues surrounding the slow, melodically limited liturgical tune, all supported by a 'walking' bass (pilgrims?), invokes a strange mixture of constriction and exaltation. Two noteworthy details are the wonderful 'enhancement' as the horns enter at the beginning of the recapitulation, and a moment of tonal ambiguity near the end, which further develops the previous D/F polarities.

The minuet-finale has posed a problem for interpretation, partly because great symphonies are 'supposed' to have four movements, partly because minuets carry associations of the galant. And yet this austerely concentrated movement is in many ways the most intense of all. Right from the start, the off-tonic beginning, unstable rhythmic motives, Neapolitan harmony, and ambiguous phrase-rhythm create an oppressive mood. No root-position tonic appears until the recapitulation and even this event is destabilized. The bass stamps out the theme one measure 'too soon', so that when the melody enters 'correctly', it engenders a remarkable rising canon, which dominates the recapitulation and seems to stretch toward the heavens, until it abruptly breaks off on a dissonant chord; the final cadences follow quietly. (Mozart is foreshadowed here, particularly the Adagio and Fugue for two pianos, K426, and the D minor Piano Concerto.) Although it would be witless to speculate how an eighteenth-century listener might have heard this movement in terms of the Passion, surely it is earnest enough to conclude this remarkable symphony.

Analysis

Analysis of the movements

Musicians

Musicians

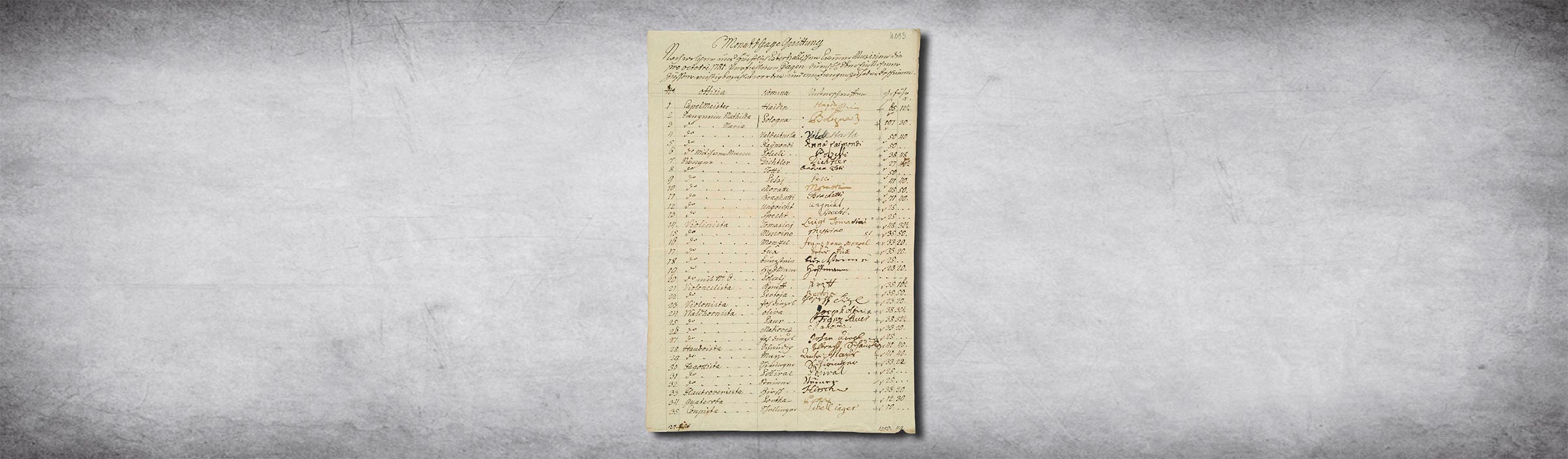

Due to the unclear time of origin of most of Haydn’s symphonies - and unlike his 13 Italian operas, where we really know the exact dates of premieres and performances - detailed and correct name lists of the orchestral musicians cannot be given. As a rough outline, his symphony works can be divided into three temporal blocks. In the first block, in the service of Count Morzin (1757-1761), in the second block, the one at the court of the Esterházys (1761-1790 but with the last symphony for the Esterház audience in 1781) and the third block, the one after Esterház (1782-1795), i.e. in Paris and London. Just for this middle block at the court of the Esterházys 1761-1781 (the last composed symphony for the Esterház audience) respectively 1790, at the end of his service at the court of Esterház we can choose Haydn’s most important musicians and “long-serving companions” and thereby extract an "all-time - all-stars orchestra".

| Flute | Franz Sigl 1761-1773 |

| Flute | Zacharias Hirsch 1777-1790 |

| Oboe | Michael Kapfer 1761-1769 |

| Oboe | Georg Kapfer 1761-1770 |

| Oboe | Anton Mayer 1782-1790 |

| Oboe | Joseph Czerwenka 1784-1790 |

| Bassoon | Johann Hinterberger 1761-1777 |

| Bassoon | Franz Czerwenka 1784-1790 |

| Bassoon | Joseph Steiner 1781-1790 |

| Horn (played violin) | Franz Pauer 1770-1790 |

| Horn (played violin) | Joseph Oliva 1770-1790 |

| Timpani or Bassoon | Caspar Peczival 1773-1790 |

| Violin | Luigi Tomasini 1761-1790 |

| Violin (leader 2. Vl) | Johann Tost 1783-1788 |

| Violin | Joseph Purgsteiner 1766-1790 |

| Violin | Joseph Dietzl 1766-1790 |

| Violin | Vito Ungricht 1777-1790 |

| Violin (most Viola) | Christian Specht 1777-1790 |

| Cello | Anton Kraft 1779-1790 |

| Violone | Carl Schieringer 1768-1790 |

Medias

Music

Antal Dorati

Joseph Haydn

The Symphonies

Philharmonia Hungarica

33 CDs, aufgenommen 1970 bis 1974, herausgegeben 1996 Decca (Universal)