43

"Merkur"

E flat major

Sinfonien um 1770-1774

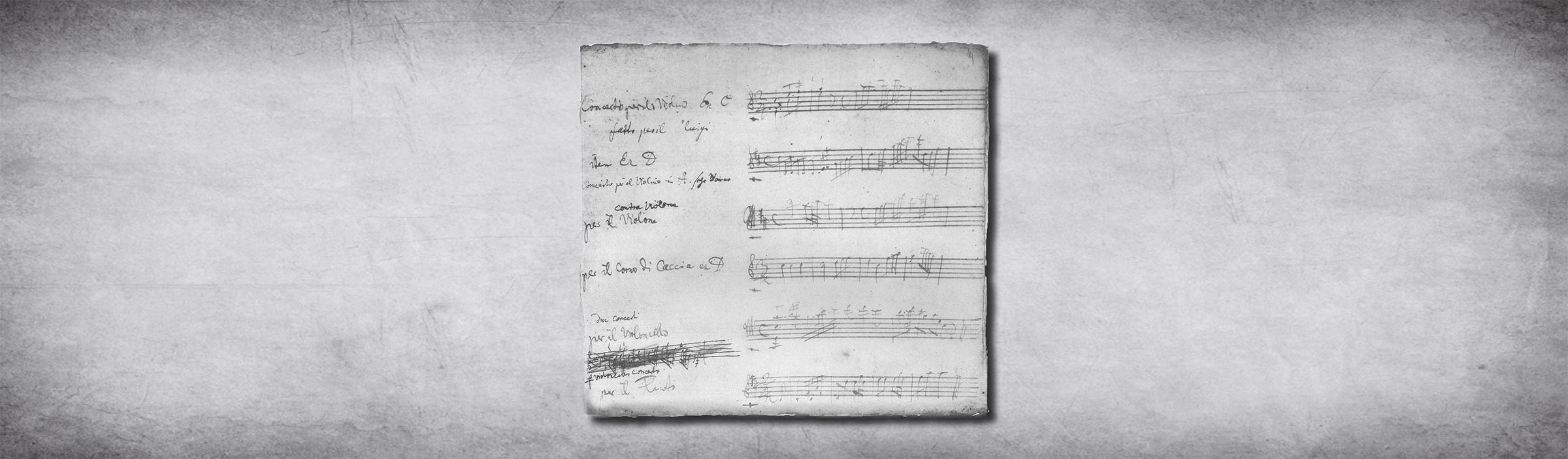

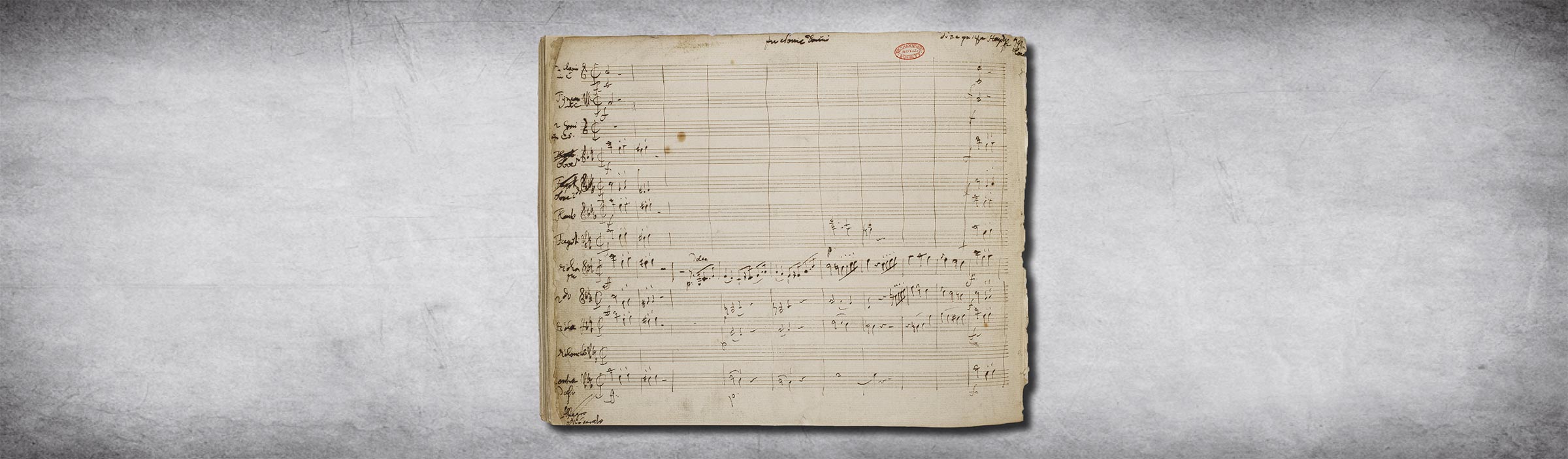

Herausgeber: Andreas Friesenhagen und Ulrich Wilker; Reihe I, Band 5b; 2013, G. Henle Verlag München

Symphony No. 43 in E flat major

The long main theme of the opening Allegro fooled even so fine a critic as Charles Rosen, who criticized it as providing 'relaxed beauty... at the price of a flaccid coordination between cadential harmonies and large-scale rhythm'.4 (This misreading forms part of his elaborate defence of the untenable notion that Haydn did not attain 'maturity' until the 1780s, along with the triumph of 'Classical style'.)5 Admittedly, the theme appears to circle somewhat aimlessly around the first inversion of the tonic triad. But that is Haydn's point. It goes on too long, too demonstratively refuses to do anything, so that we become increasingly uneasy, more and more needful of hearing something different which he finally provides when the violins, with a sudden forte, plunge down in tremolo semiquavers and the harmonic rhythm accelerates, leading to a very strong cadence that closes the first group and is elided to the vigorous transition.

The remainder of the exposition maintains the vigorous tone, except for a brief quiet passage that recalls the 'static' opening. But (after the exposition repeat) the development soon leads to yet another repetition of parts of the opening theme, in the tonic. This procedure is neither a 'false recapitulation' (which comes midway through a development section) nor a defect of form, but what I call an 'immediate reprise'; that is, a sophisticated variant of the older practice in which the development began with a two-fold statement of the main theme, first in the dominant, then in the tonic.6 Naturally, Haydn soon strikes out into other keys; before long, however, he breaks off yet again, and a threefold sequence based on the opening phrase leads to the recapitulation proper. (A similar transition is found in the String Quartet in D major, op. 20 no. 4.) The 'excessive' persistence of the main theme is thus wittily inscribed into the form as a whole.

The Adagio rings yet another change on the sprightly profundity so characteristic of Haydn's slow movements. The sectional construction (first group, transition, second group; development; recapitulation) is unusually clear by Haydn's standards; he rarely approaches this 'Mozartian' quality of every bar being as if foreordained. Perhaps this is why he inserted a chromatic 'sighing' passage into the second group, and utilized it again 'too long' for the entire second half of the development.

The vigorous minuet is clear in outline, although it includes subtle variations in the treatment of the 'long-short' motive and the phrase-rhythm; its quiet concluding phrase recalls the 'static' opening theme of the symphony. In the trio, Haydn proves that a single four-bar phrase (2+2) heard four times in close succession is not boring, when it prepares, first a cadence in the dominant, then one in the tonic.

In the Allegro Finale, Haydn's underlying eccentricity becomes more overt. The quiet main theme in rapid upward skips is demonstratively irregular in phrasing. Once we are off to the races, the music stops 'too often'; these pauses are sometimes followed by long expanded upbeats for the violins alone, sometimes by chromatic progressions in long notes. In the development, one of those expanded upbeats jokingly leads into the recapitulation. This section is unusually regular and cadential too much so: after the repeat of the second 'half' of the movement it is followed, very unusually, by a long coda. This not only outdoes everything else in eccentricity, it systematically avoids cadencing until the very last moment.

The silly nickname 'Mercury' became attached to this symphony only in the nineteenth century; it is entirely lacking in relevance.

Analysis

Analysis of the movements

Musicians

Musicians

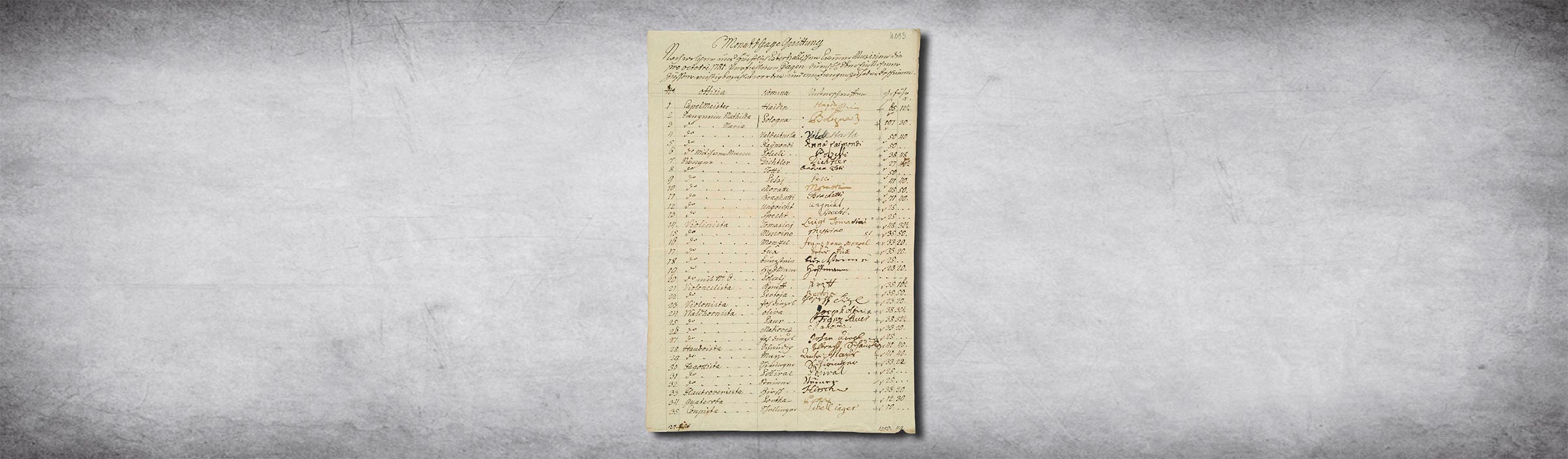

Due to the unclear time of origin of most of Haydn’s symphonies - and unlike his 13 Italian operas, where we really know the exact dates of premieres and performances - detailed and correct name lists of the orchestral musicians cannot be given. As a rough outline, his symphony works can be divided into three temporal blocks. In the first block, in the service of Count Morzin (1757-1761), in the second block, the one at the court of the Esterházys (1761-1790 but with the last symphony for the Esterház audience in 1781) and the third block, the one after Esterház (1782-1795), i.e. in Paris and London. Just for this middle block at the court of the Esterházys 1761-1781 (the last composed symphony for the Esterház audience) respectively 1790, at the end of his service at the court of Esterház we can choose Haydn’s most important musicians and “long-serving companions” and thereby extract an "all-time - all-stars orchestra".

| Flute | Franz Sigl 1761-1773 |

| Flute | Zacharias Hirsch 1777-1790 |

| Oboe | Michael Kapfer 1761-1769 |

| Oboe | Georg Kapfer 1761-1770 |

| Oboe | Anton Mayer 1782-1790 |

| Oboe | Joseph Czerwenka 1784-1790 |

| Bassoon | Johann Hinterberger 1761-1777 |

| Bassoon | Franz Czerwenka 1784-1790 |

| Bassoon | Joseph Steiner 1781-1790 |

| Horn (played violin) | Franz Pauer 1770-1790 |

| Horn (played violin) | Joseph Oliva 1770-1790 |

| Timpani or Bassoon | Caspar Peczival 1773-1790 |

| Violin | Luigi Tomasini 1761-1790 |

| Violin (leader 2. Vl) | Johann Tost 1783-1788 |

| Violin | Joseph Purgsteiner 1766-1790 |

| Violin | Joseph Dietzl 1766-1790 |

| Violin | Vito Ungricht 1777-1790 |

| Violin (most Viola) | Christian Specht 1777-1790 |

| Cello | Anton Kraft 1779-1790 |

| Violone | Carl Schieringer 1768-1790 |

Medias

Music

Antal Dorati

Joseph Haydn

The Symphonies

Philharmonia Hungarica

33 CDs, aufgenommen 1970 bis 1974, herausgegeben 1996 Decca (Universal)