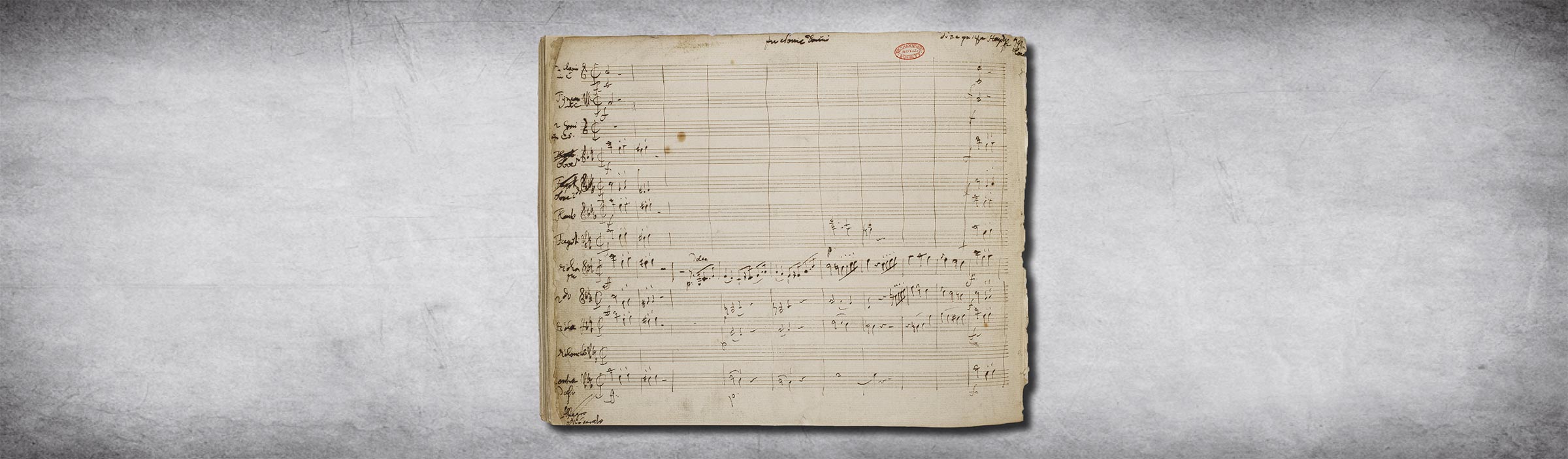

45

"Abschiedssinfonie"

f sharp minor

Sinfonien 1767-1772

Herausgeber: Carl-Gabriel Stellan Mörner; Reihe I, Band 6; G. Henle Verlag München

Symphony No. 45 in F sharp minor ('Farewell')

This is the most famous among Haydn's 'Sturm und Drang' symphonies, owing both to its programme and to its unique style and construction. Every year, the Esterházy court spent the warm season at Prince Nikolaus's new and splendid, but remote, summer castle 'Eszterháza'. With the exception of Haydn and a few other privileged individuals, the musicians were required to leave their families behind in Eisenstadt. Haydn's biographer Griesinger tells the story as follows:

One year, against his usual custom, the prince determined to extend his stay in Eszterháza for several weeks. The ardent married men, thrown into utter consternation, turned to Haydn and asked him to help. Haydn hit upon the idea of writing a symphony ... in which, one after the other, the instruments fall silent. At the first opportunity, this symphony was performed in the prince's presence. Each of the musicians was instructed that, as soon as his part had come to an end, he should extinguish his light, pack up his music, and leave with his instrument under his arm. The prince and the audience at once understood the point of this pantomime; the next day came the order for the departure from Eszterháza. To be sure, the nickname 'Farewell' stands neither in Haydn's autograph (the only surviving authentic source) nor in any other eighteenth-century musical source; it probably originated in France in the 1780s. Nor does the autograph provide any indication of leaving the hall or other unusual goings-on. On the other hand, almost all later sources, both musical and anecdotal, specify this; indeed, the German version of the nickname ('Abschiedssinfonie') was widely disseminated by 1800; Griesinger himself uses it. In any case, Haydn's audiences would surely have understood such a symphony in programmatic terms.

The 'Farewell' Symphony is arguably Haydn's most extraordinary composition. It is the only known eighteenth-century symphony in F sharp. It is his only symphony in five real movements; the last two constitute a run-on 'double finale', a Presto and the concluding 'farewell' movement; the latter is not only an Adagio, but ends in a different key from that in which it begins. The cycle is so highly organized as to justify the epithet 'through-composed'; the entire symphony prepares, and is resolved by, the apotheosis of the 'farewell' ending. After 1772, the earliest work that so much as approached it in these respects was Beethoven's Fifth Symphony.

All this is carried out by means of an unusual 'double cycle'. Each cycle entails the same sequence of three structural keys: F sharp minor, A major, and F sharp major. In the first cycle, this comprises the Allegro assai (f sharp), the Adagio (A), and the minuet (F sharp); in the second, the Presto (f sharp) and the two parts of the 'farewell' movement (A moving to F sharp). In addition, each cycle incorporates an extended decrescendo from loud to very soft, and from a fast, agitated style to a slower, calmer one; the final phrase of the minuet, for the violins alone, off-tonic and pianissimo, foreshadows the end of the symphony. Yet the end is 'more so' that is, less: two solo violins, muted, unaccompanied, for fifteen Adagio measures. As a 'negative climax', it has never been surpassed.

At the same time, the double cycle articulates an overall progression from instability to stability. In the first three movements, musical coherence seems almost to break down; all three are tonally unstable and have inadequate closure. The Allegro assai, in sonata form, is the most savage movement Haydn ever composed; its rhythms are obsessively, almost mechanically, regular. The tonic of the opening theme is projected 'weakly'; the second group feints towards the relative, A major, but cannot cadence there, ending instead in the dominant minor (uniquely in Haydn's fast sonata-form movement). In the recapitulation, the tonic is brutally undermined just four bars after it enters, and its restoration, after the most violent music in the movement, is too little, too late.

An inexplicable event is the extended piano interlude in D major that makes up the entire second half of the development. It 'floats' in the high register; its breathless phrasing contradicts its surface regularity; its internal form is self-contradictory: apparently a quiet moment of repose, it incorporates and extends the principle of instability that governs the entire movement. It remains unresolved and unexplained. And since the remainder of this movement entirely ignores it, that explanation can only come elsewhere on a level that involves the entire symphony.

The Adagio and minuet are also unstable, albeit in different ways from the Allegro assai (and each other). To be sure, the sonata-form Adagio eases the tension; it is squarely in the relative A major, and its themes are clear periods, its keys strongly established. But the themes are troubled by rhythmic disunity and cannot articulate their own cadences, and the entire second group is burdened with major/minor chromaticism. In the minuet and trio, we finally hear F sharp major as a key. This key cannot suppress echoes of the minor, rudely disruptive in the minuet (the bass entry in the third bar), wistfully unintegrated in the trio. All the melodic entries are off-tonic and lack bass; even their ostensibly clear forms are ambiguous. The last thing we hear is the minuet's inconclusive off-tonic tag.

The double finale, comprising the Presto and the 'farewell' Adagio, is entirely progressive, not merely in being run-on and in the 'action' at the end, but in thematic development and formal and tonal structure. Closure is systematically postponed until the final section of the 'farewell' movement. The farewell procedure is progressive in its own right: a gradual and systematic reduction of the ensemble to two solo muted violins.

In contrast to the first three movements, however, the musical language is now normal. The F sharp minor Presto, in many respects a typical symphonic finale of the period, is in very clear sonata form, except that the recapitulation breaks off at the last minute and leads back to a structural dominant. This does not resolve, but proceeds abruptly to A major and the calm farewell music. The farewell movement is in two main parts: (I) a binary movement in A, at the ends of whose two sections the 'farewell' theme itself is heard in oboes and horns; and (2) a compressed recapitulation and coda in F sharp major. They are linked by a modulating transition for the double-bass, also on the farewell theme, which 'recaptures' the home dominant from the end of the Presto. Hence the concluding section in F sharp major, unlike the minuet, resolves the music that precedes it.

This resolution is not only tonal, but formal and gestural. The music becomes increasingly diatonic; the final section, for the two muted violins and viola, includes not a single accidental. And the very last, codetta measures revert to the 'farewell' theme itself. The form is as logical and coherent as in any other movement by Haydn.

What is more, this ending has been prepared, precisely by the most problematical earlier passage: the D major interlude in the Allegro assai: 'insubstantial', for strings alone, beginning without bass, soft, legato, tuneful, regular in phrasing. Now, at the end, its register, style, and mood return in the tonic. Though not even hinting at a thematic recall, the ending thus implicitly recapitulates the interlude; the 'sonata principle' is affirmed, over the course of the entire symphony.

This ending suggests an interpretation of the entire symphony not merely the finale in terms of the programme. With winter approaching, Haydn's musicians are stuck in the barren splendour of Eszterhaza castle; they desperately want to go home to their families. Their frustration is vividly projected by the unstable, passionately unfulfilled Allegro assai in F sharp minor. But this is no ordinary key. Not only was it difficult for intonation, it was literally unheard of as an overall tonic in later-eighteenth-century orchestral music. F sharp minor thus represents a remote and inhospitable part of the musical universe just as Eszterhaza lay in a remote and inhospitable district. (Haydn more than once referred to it as an Einöde, a wasteland.)

Equally obviously, the musicians' yearning for home is symbolized by the parallel major, the only sonority which can really resolve the tension and dissonance of a minor key. But this key is F sharp major: extremely distant (six steps from C on the circle of fifths), a region almost never dreamed of, let alone attained, by orchestral musicians. If this is 'home', it will be reachable (if at all) only at the end of a long and arduous journey.

In the wild desert of the Allegro assai, no major key can function. Even the interlude is insubstantial, unanalysable; in short, a mirage. Similarly, the A major and F sharp major of the Adagio and minuet, which remain isolated from each other and internally unstable, offer no real resolution.

By contrast, the Presto and the farewell movement traverse all the steps of the journey; at the end, F sharp major resolves its own dominant and all the preceding keys, and is repeatedly confirmed by strong cadences, purged of all dissonance and chromaticism, and informed by pure and expressive themes. Haydn's musicians have earned the right to call it 'home' except that it remains distant, ethereal. The 'Farewell' Symphony's vision of home may remain unattainable. And rightly so: the musicians' condition is one of absence; their goal is merely a cherished hope.

This does not compromise the symphony's psychological truth. Even Prince Esterházy did not remain immune, however little his personal comfort may have been at stake. We too, more than two centuries later, respond to the genius of Haydn's musical vision: this miraculous balance of absence and fulfillment, of desire gratified only in longing.

Analysis

Analysis of the movements

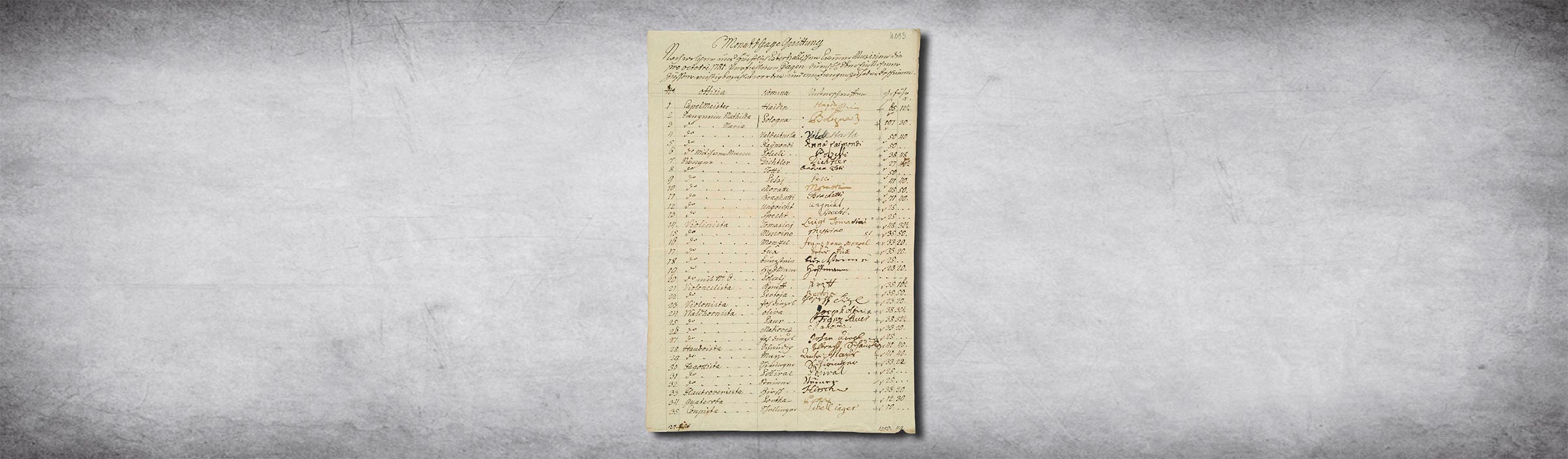

Musicians

Musicians

Due to the unclear time of origin of most of Haydn’s symphonies - and unlike his 13 Italian operas, where we really know the exact dates of premieres and performances - detailed and correct name lists of the orchestral musicians cannot be given. As a rough outline, his symphony works can be divided into three temporal blocks. In the first block, in the service of Count Morzin (1757-1761), in the second block, the one at the court of the Esterházys (1761-1790 but with the last symphony for the Esterház audience in 1781) and the third block, the one after Esterház (1782-1795), i.e. in Paris and London. Just for this middle block at the court of the Esterházys 1761-1781 (the last composed symphony for the Esterház audience) respectively 1790, at the end of his service at the court of Esterház we can choose Haydn’s most important musicians and “long-serving companions” and thereby extract an "all-time - all-stars orchestra".

| Flute | Franz Sigl 1761-1773 |

| Flute | Zacharias Hirsch 1777-1790 |

| Oboe | Michael Kapfer 1761-1769 |

| Oboe | Georg Kapfer 1761-1770 |

| Oboe | Anton Mayer 1782-1790 |

| Oboe | Joseph Czerwenka 1784-1790 |

| Bassoon | Johann Hinterberger 1761-1777 |

| Bassoon | Franz Czerwenka 1784-1790 |

| Bassoon | Joseph Steiner 1781-1790 |

| Horn (played violin) | Franz Pauer 1770-1790 |

| Horn (played violin) | Joseph Oliva 1770-1790 |

| Timpani or Bassoon | Caspar Peczival 1773-1790 |

| Violin | Luigi Tomasini 1761-1790 |

| Violin (leader 2. Vl) | Johann Tost 1783-1788 |

| Violin | Joseph Purgsteiner 1766-1790 |

| Violin | Joseph Dietzl 1766-1790 |

| Violin | Vito Ungricht 1777-1790 |

| Violin (most Viola) | Christian Specht 1777-1790 |

| Cello | Anton Kraft 1779-1790 |

| Violone | Carl Schieringer 1768-1790 |

Medias

Music

Antal Dorati

Joseph Haydn

The Symphonies

Philharmonia Hungarica

33 CDs, aufgenommen 1970 bis 1974, herausgegeben 1996 Decca (Universal)