59

"Feuersinfonie"

A major

Sinfonien um 1766-1769

Herausgeber: Andreas Friesenhagen und Christin Heitmann; Reihe I, Band 5a; 2008, G. Henle Verlag München

Symphony No. 59 in A major

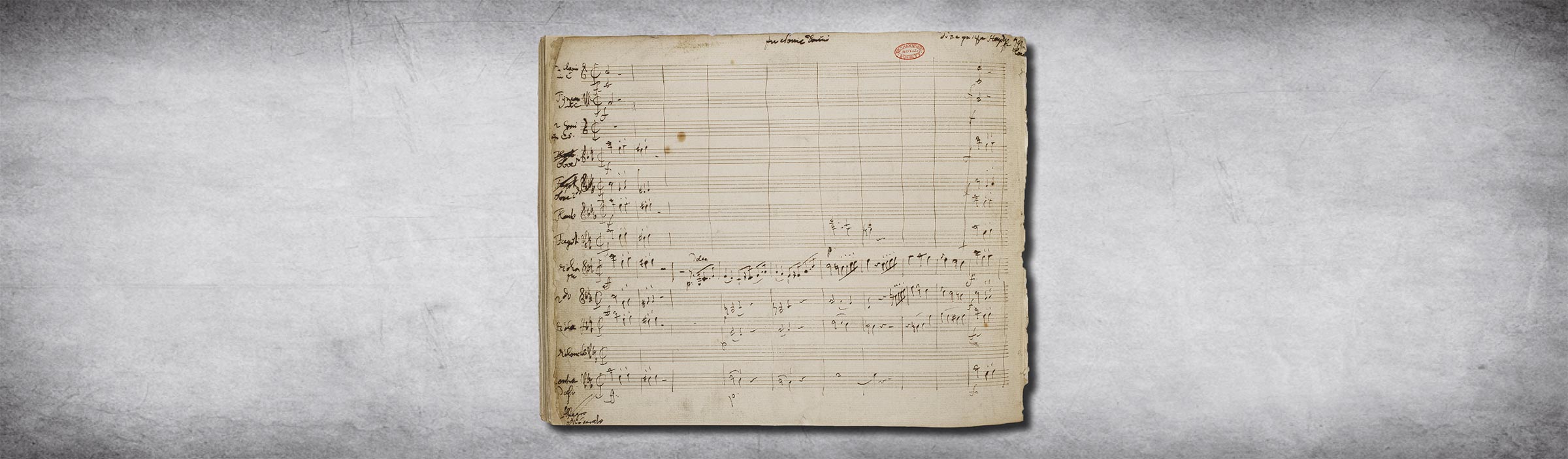

Three Haydn symphonies in the key of A from the late 1760s and early 1770s are among his most 'theatrical': Nos. 59 and 65 in this volume, and the slightly later No. 64. (The nickname 'Fire', like so many, is spurious: it appears only on one late, inauthentic source; nor is this work off. 1768, as one often reads, related to a play titled Die Feuersbrunst performed at Eszterháza in 1774, still less to the Singspiel of the same name - which is in any case a pasticcio, not a work of Haydn.)2 But it is easy to believe that Symphony No. 59 might have originated at least in part as incidental music. The Presto (a very unusual tempo for an opening movement after the 1750s), with its opening octave leap and rushing scales underneath shifting-rhythmed repeated notes, at once suggests a crowd of confused conspirators; and it is theatrical indeed when they suddenly halt on a foreign chord, piano, moving to the dominant and a pause, rather in the manner of a slow introduction - a most incongruous type of 'opening' gesture, when juxtaposed with the actual beginning. No mere theatricalism, however, is Haydn's unpredictable, yet coherent play with these motives throughout the movement; even that piano halt not only returns several times (always varied) but, intensified into pianissimo, has the final word.

But the Andante o più tosto allegretto in the tonic minor is far stranger. (The minor keys of A, E, and B, associated with the 'sharp' side of the tonal spectrum, often stimulated Haydn to adopt an exotic, 'Hungarian' or 'Balkan' air.) A spare two-part theme soon leads to a completely different cantabile theme in the relative major (C), developed at great length indeed at excessive length: a characteristic of Haydn's incidental music. When the cadence is reached at last, the same theme leads back to the dominant and a brief reprise of the first theme. Then comes the real surprise: the major-mode theme immediately enters again, in A major, along with the (utterly unexpected) oboes and horns: a ravishing yet peculiar effect. The peculiarity is only heightened by yet another, apparently unmotivated recall of the opening theme, fortissimo, which disappears as quickly as it enters, leaving the entirety of the overlong major theme to be recapitulated.

The minuet begins with the same motive as the Andante (a relatively early example of Haydn's increasingly strong tendency to create motivic links among the several movements in the cycle); the trio again resorts to the tonic minor and to strings alone. The sonata-form finale, Allegro assai, begins with an unaccompanied horn-call in long notes (an effect that Haydn will vary in one of his latest and greatest finales: of the 'Drum Roll' Symphony, No. 103); this horn-call alternates with an oboe melody in fast notes. The continuation, with a trilled note for the horns, is amusing enough, but a better joke follows at once: the strings enter and force these motivic scraps to pretend that they are going to become a fugue. Nothing could be less likely; sure enough, after only four bars we are off to the races in good finale style - until the development, when we are treated to a proper fugato after all! Further surprises follow in the recapitulation; Haydn even indulges in an extensive coda, with a last witty variation of his scrappy theme.

Analysis

Analysis of the movements

Musicians

Musicians

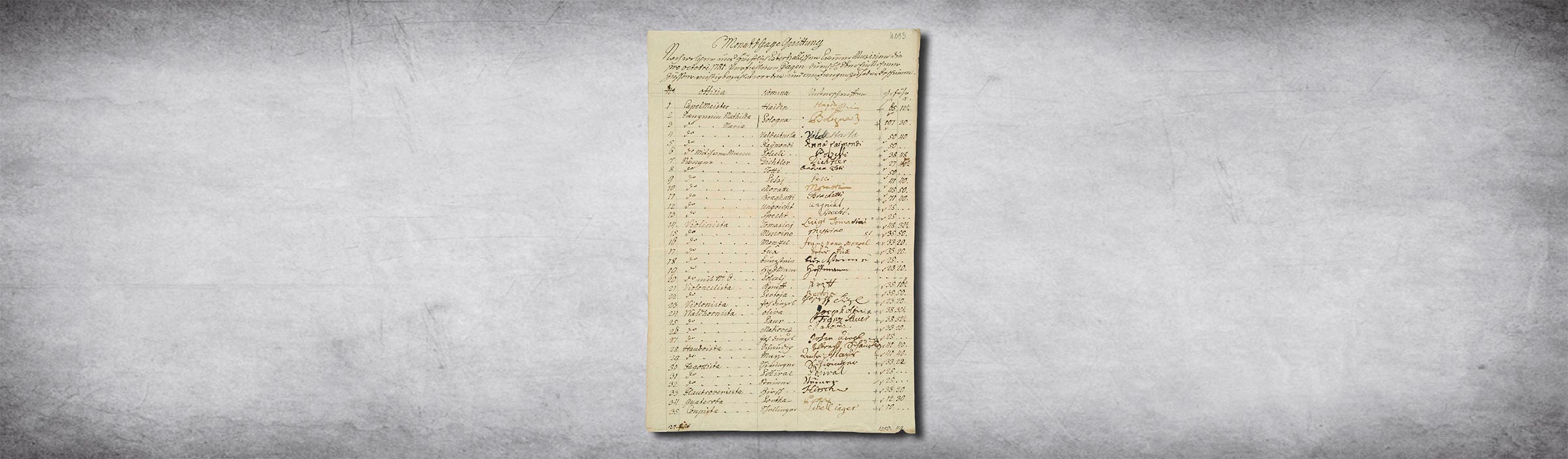

Due to the unclear time of origin of most of Haydn’s symphonies - and unlike his 13 Italian operas, where we really know the exact dates of premieres and performances - detailed and correct name lists of the orchestral musicians cannot be given. As a rough outline, his symphony works can be divided into three temporal blocks. In the first block, in the service of Count Morzin (1757-1761), in the second block, the one at the court of the Esterházys (1761-1790 but with the last symphony for the Esterház audience in 1781) and the third block, the one after Esterház (1782-1795), i.e. in Paris and London. Just for this middle block at the court of the Esterházys 1761-1781 (the last composed symphony for the Esterház audience) respectively 1790, at the end of his service at the court of Esterház we can choose Haydn’s most important musicians and “long-serving companions” and thereby extract an "all-time - all-stars orchestra".

| Flute | Franz Sigl 1761-1773 |

| Flute | Zacharias Hirsch 1777-1790 |

| Oboe | Michael Kapfer 1761-1769 |

| Oboe | Georg Kapfer 1761-1770 |

| Oboe | Anton Mayer 1782-1790 |

| Oboe | Joseph Czerwenka 1784-1790 |

| Bassoon | Johann Hinterberger 1761-1777 |

| Bassoon | Franz Czerwenka 1784-1790 |

| Bassoon | Joseph Steiner 1781-1790 |

| Horn (played violin) | Franz Pauer 1770-1790 |

| Horn (played violin) | Joseph Oliva 1770-1790 |

| Timpani or Bassoon | Caspar Peczival 1773-1790 |

| Violin | Luigi Tomasini 1761-1790 |

| Violin (leader 2. Vl) | Johann Tost 1783-1788 |

| Violin | Joseph Purgsteiner 1766-1790 |

| Violin | Joseph Dietzl 1766-1790 |

| Violin | Vito Ungricht 1777-1790 |

| Violin (most Viola) | Christian Specht 1777-1790 |

| Cello | Anton Kraft 1779-1790 |

| Violone | Carl Schieringer 1768-1790 |

Medias

Music

Antal Dorati

Joseph Haydn

The Symphonies

Philharmonia Hungarica

33 CDs, aufgenommen 1970 bis 1974, herausgegeben 1996 Decca (Universal)